When business executive Edwin Land was on a family vacation decades ago, he took a picture of his daughter, who was three at the time. She wanted to see the picture right away and asked him why she couldn’t see it right then.

That simple question from a child pushed Land to carry the inquiry further by asking what it would take to take instant photography to the market. His work on this question led him to some profound insights, which came in handy since he was a cofounder of Polaroid.

Answering his daughter’s simple but powerful question transformed the company, disrupted their industry, and led to the sale of more than 150 million units of their new instant camera. The fundamental insight came not from the obvious question of how to improve the camera but rather from a wholly different type of question.

It turns out that this kind of provocative questioning is a key driver of transformative innovation.

The Innovator’s DNA

Innovation scholars Jeff Dyer, Hal Gregersen, and Clayton Christensen sought to determine what the world’s best innovators do to create transformative products, services, and companies. They wondered what distinguishes these innovative entrepreneurs and executives from ordinary managers.

To answer these questions, they interviewed nearly a hundred inventors of revolutionary products and services, as well as founders and CEOs of companies built on innovative business ideas. They studied CEOs who drove innovation in their companies, and they surveyed more than 500 innovators and more than 5,000 executives in more than 75 countries.

Through this work, they found five discovery skills that drive disruptive innovation: associating, questioning, observing, networking, and experimenting. Here we focus on questioning. In their book, The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators, they wrote the following:

“Our research found that not only do innovators ask more questions than noninnovators, they also ask more provocative ones…. Innovators… ignore safe questions and opt for crazy ones, challenging the status quo and often threatening the powers that be with uncommon intensity and frequency.”

These scholars were not alone in this finding. In his book, Creativity, the late psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi noted that Nobel Laureates were much better at achieving breakthroughs once they found the right question to reframe the problem they were working on.

Leadership Derailers Assessment

Take this assessment to identify what’s inhibiting your leadership effectiveness. It will help you develop self-awareness and identify ways to improve your leadership.

Hövding

When Anna Haupt and Terese Alstin were studying Industrial Design at the University of Lund in Sweden, they asked a question that would change their lives:

Do bike helmets have to be so big and bulky?

Bicycles have been around for centuries. They’re an incredible invention but they do come with the problem of crashes and head injuries. In the early 1900s, bicycle helmets were strips of leather-covered padding, and in the ensuring decades hard helmets spread. They were much safer but a real hassle to carry around and store.

As part of their master’s thesis in 2005, Anna and Terese designed the world’s first airbag bicycle helmet, which they called Hövding. After years of research and development, they launched it on the market.

It’s actually a scarf that bikers wear around their neck. Sensors in the collar measure vibrations and only react to critical values, drawn from accelerometer data with measurements taken hundreds of times a second. If the accelerometers detect unusual movements that match a crash profile, they deploy the airbag around the cyclist’s head with astonishing speed. The founders spent years testing potential scenarios with stuntmen to ensure safety and reliability.

They won a business plan competition, launched the company with the proceeds, and won a prestigious design award. (For more, see this “Invisible Bike Helmet” video.)

Dell

Similar questioning helped entrepreneur Michael Dell create his computer empire. As a university student, he was curious about computers and started playing around with them. Here’s Dell in his own words:

“I was a frustrated consumer, and I would open computers up, I’d take them apart; I knew what was inside them and would observe that $600 worth of parts were sold for $3,000. That didn’t make any sense to me. I really questioned why it cost five times more to buy the darn thing than the parts cost.”

This question launched him on a multi-year quest that led to a disruptive new business model in the industry. Unlike other manufacturers, Dell purchased parts based on orders already in hand, and only assembled computers for immediate delivery. With no inventory or spare parts to store, the company enjoyed dramatically lower overhead and passed the savings on to customers. With high sales volume due to lower prices, Dell could insist that its suppliers maintain warehouses near its factories, speeding up the processing of orders, while the suppliers bore the cost of storing unsold parts. High sales volume made the arrangement profitable for all concerned.

The company outperformed its rivals in a tough industry for more than a decade, eventually becoming the largest, fastest growing, and most profitable personal computer manufacturer in the world. The business model included digital data exchange systems with suppliers, built-to-order products (helping the company develop relationships with customers and deliver exactly what they want), direct sales (skipping resellers), lower inventory costs (yielding better working capital), and more. Importantly, the business model was hard to copy because its rivals were wedded to their existing distribution channels. And it all started with him asking a provocative question in his dorm room.

Personal Values Exercise

Complete this exercise to identify your personal values. It will help you develop self-awareness, including clarity about what’s most important to you in life and work, and serve as a safe harbor for you to return to when things are tough.

How to Get Better at Questioning

So, how we can get better at this kind of questioning to drive innovation in our own context? Dyer, Gregersen, and Christensen advise the following:

Engage not just in brainstorming but also in “question-storming” / a “question burst.” This involves coming up not with ideas for solutions to address a problem but with questions about the problem and its context, constituents, and challenges. The rules: No answers allowed. Document every question mentioned without exception. No commentary or judgment.

Gregersen advises shooting for a large number of questions (e.g., 20 or 50). About halfway through, the process may stall. It’s important to keep going, because often that’s where some of the greatest questions arise. Once the question list is packed, circle back and home in on intriguing, provocative, or concerning questions to explore further.

The process can be an important compliment to traditional brainstorming, which can stall when people struggle to generate new solution ideas. Gregersen reports that, about 80% of the time, a question burst process yields at least one question that provides a powerful new angle for making progress.

Maintain a high question/answer ratio. Make sure people are focusing on asking a lot of good questions and not seeking quick solutions. Often, those solutions prove unworkable. Value good questions as highly as good answers.

Keep a question notebook (like Richard Branson). Fill it with the things that mystify you or that don’t seem quite right. Questions like the following: “Why is there such a long wait for…?” “Why are so many customers frustrated by their experience with…?” “How can these breakthroughs from industry X apply to our industry?”

Reframe the issue at hand from a challenge into a question. For example, a retailer can reframe the challenge of reducing customer waiting time to a question about how to make customers more comfortable with waiting time that can’t be reduced (e.g., via entertainment and stimulation). Note that both forms of innovation and improvement can proceed in parallel.

Play the “devil’s advocate” in discussions about potential solutions, asking hard-hitting questions. This will help avoid common problems like groupthink. Pierre Omidyar is famous for doing this at eBay.

Don’t accept anything at face value: question all assumptions and look for potential biases in your reasoning or process.

Pay attention to what questions are not being asked. Be as thorough as possible, taking nothing for granted.

Why Questioning Can Be So Challenging

It may sound obvious that questioning is important and helpful, but doing it in practice is often harder than it sounds. Why? For many reasons. First, because many of us feel stupid when we ask questions. Today’s world, from schools to boardrooms, places a premium on answers, not questions. It takes courage and confidence to ask a lot of questions.

Many people don’t ask questions because they don’t want to come across as being difficult or ornery. And many workers hesitate to ask their managers tough or provocative questions for fear of risking their job or bonus (a sign, by the way, that psychological safety is missing).

Alignment Scorecard

When organizations aren’t aligned, it can reduce performance dramatically and cause frustration and dysfunction. With this Alignment Scorecard, you can assess your organization’s level of alignment and make plans for improving it.

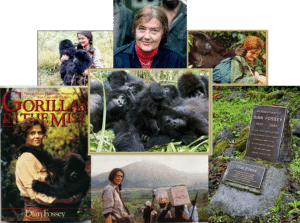

Gorilla Questions

My favorite story about the power of questions comes from the filming of “Gorillas in the Mist,” a production meant to tell the story of Dian Fossey’s groundbreaking research on primates. Fossey was an American zoologist who studied gorilla groups extensively for 18 years in the remote mountain forests of Rwanda.

The film production was a logistical nightmare because it involved filming hundreds of animals at an altitude of about 11,000 feet above sea level in the mountains of Rwanda. The lead actress, Sigourney Weaver, and crew had to climb thousands of feet from their base camp every day to reach the shooting location while lugging heavy equipment.

To get the on-location sequences needed, they essentially needed the gorillas to “act” in accordance with the screenplay. If that didn’t pan out, their backup plan was go back and film human actors in gorilla suits on a soundstage in Hollywood. Clearly, that would seriously detract from the film’s authenticity and quality.

As film executives were debating this intensely, an intern spoke up and asked a provocative question:

Why don’t we let the gorillas write the story?

The idea was as simple as it was revolutionary. Instead of trying to get the gorillas to fit into the contours of the screenplay, have the film crew capture the gorillas doing what they do naturally, then revise the script as needed.

With that new approach, they filmed the movie for about half of the original budget, and it won two Golden Globes and earned five Academy Awards nominations.

According to film producer Peter Guber, it speaks to the importance of asking good questions and finding people who add new perspectives—and listening to them (regardless of their status in the organization).

Reflection Questions

- To what extent are you focusing on powerful and provocative questions in your organization?

- Which of these questioning techniques with you try?

Tools for You

- Leadership Derailers Assessment to help you identify what’s inhibiting your leadership effectiveness

- Personal Values Exercise to help you determine and clarify what’s most important to you

- Alignment Scorecard to help you assess your organization’s level of alignment

Related Articles

Postscript: Quotations on Questioning and Innovation

- “The power to question is the basis of all human progress.” -Indira Gandhi, former prime minister of India

- “If you want to be creative, go where your questions lead you.” -Louis L’Amour, novelist

- “If I only had the right question…. the formulation of a problem is often more important than its solution.” -Albert Einstein

- “I learned to push the envelope when it comes to asking questions or making requests. And if you hear ‘that’s not possible,’ then ask ‘what is possible,’ instead of just saying thank you and leaving.” -Emily Weiss, founder, Glossier

- “The best creative solutions don’t come from finding good answers to the questions that are presented. They come from inventing new questions.” -Seth Godin, entrepreneur, best-selling author, and blogger

- “Once you figure out the question, then the answer is relatively easy. I came to the conclusion that really we should aspire to increase the scope and scale of human consciousness in order to better understand what questions to ask.” -Elon Musk, quoted in Ashlee Vance, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future

- “Question the unquestionable.” -Ratan Tata, chairman, Tata Group

- “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity. The important thing is not to stop questioning.” -Albert Einstein

- “Innovative companies are almost always led by innovative leaders.” Jeff Dyer, Hal Gregersen, Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators

Appendix: More Examples of Questioning & Innovation

We see the power of such questioning in many industries:

Toyota

Taiichi Ohno made a “five whys” questioning process a central part of the wildly successful Toyota Production System. Workers ask why at least five times when they encounter a problem, helping them discover the root causes of the problem.

Procter & Gamble

Instead of asking straightforward and obvious questions, former CEO A.G. Lafley would look for counterintuitive and revealing ones. Instead of asking how P&G could help customers clean their floors and toilets, for example, he’d ask how the company could give them their weekends back. Swiffer, anyone?

Apple

When it came to music (MP3) players, instead of asking what the company should add to them, they instead asked why they’re so crappy and hard to use. That led to the development of the iPod, with its sleek design and elegant simplicity—and a precursor to the iPhone. After returning to Apple, Steve Jobs would ask his colleagues what they’d do if money were no object, freeing them up to think much bigger and bolder. Think different, indeed.

E-Tickets

When David Neeleman started a charter airline, Morris Air, he noticed the problem of lost paper tickets, which was incredibly frustrating for travelers and airlines alike. After hearing so many complaints, he asked why airlines treat tickets like cash and whether there isn’t a better way. That led to the idea of giving customers a code associated with their ticket that they could redeem with their identification. The insight led to e-tickets, which spread like wildfire in the industry. Neeleman went on to start JetBlue years later.

Angiotech Pharmaceuticals

Founder Dr. William Hunter changed the standard question from how to build a better stent to what the body does to stents that makes them fail. Following that line of inquiry led to a blockbuster product.

Traffic Lights

Intersections are the most dangerous parts of cities. Nobody likes to wait for the light to change so they can cross the street. So, some designers asked themselves the question:

What would happen if we made waiting fun?

They got to work and created a “dancing traffic light” in Lisbon, Portugal that entertains people as they wait to cross. The result: 81% more people stopped at the red light (and had fun while doing so).

Pasteurization

French biologist and chemist Louis Pasteur asked what causes wine to sour. That question led to his invention of the technique of treating milk and wine to stop bacterial contamination, now called “pasteurization.”

Triple Crown Leadership Newsletter

Join our community. Sign up now and get our monthly inspirations (new articles, announcements, opportunities, resources, and more). Welcome!

+++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, and TEDx speaker on leadership and personal development. He is co-author of three books, including Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations, a winner of the International Book Awards and written with his father, Bob Vanourek. Check out their Leadership Derailers Assessment or get Gregg’s monthly newsletter. If you found value in this, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!