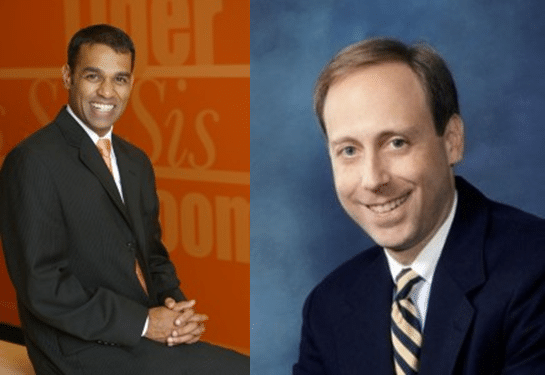

Interview with Raj Vinnakota and Eric Adler

Co-Founders and Managing Directors, The SEED Foundation

Leaders Speak Series

The SEED Foundation partners with urban communities to provide educational opportunities that prepare underserved students for success in college and beyond. SEED’s innovative model integrates a rigorous academic program with a nurturing boarding program, which teaches life skills and provides a safe and secure environment. In 1998 SEED created the first college-preparatory, public boarding school in the U.S. Here are excerpts of our interview with Raj Vinnakota and Eric Adler for our book, Triple Crown Leadership:

How would you describe SEED’s leadership approach?

Vinnakota: It stems from the conversation that Eric and I had the second time that we met, the same day we decided to leave our jobs and work together to start The SEED Foundation.

After the end of two lengthy days of debate about what kind of school to open—there was a group of about 12 people involved in that—Eric and I were the only two left on Sunday late afternoon. We decided that we wanted to start this project together to open the nation’s first urban, public boarding school.

We decided the only way this will work is if we each have 50 percent ownership—a fifty-fifty partnership. That had some implications for us: if we disagree about something, we’re stuck with each other. We have to sit and talk and discuss and argue and come to a conclusion. Only at that point can we make a decision because neither of us has a majority stake in the organization. We’re equal partners. That will require us to get to know each other very, very well and to be able to interact in such a way that we can always come to decisions.

It also means that, when one of us is not at the table for a discussion, we need to be able to take that person’s view into account. We need to be able to go back and say, “Thanks for that offer, I have to go back and talk to my partner.” Or, if we feel comfortable enough that we know what the partner will say, we need to be able to speak for both of us. Or, even more important, if we know that our partner will actually disagree with our decision, is to be able to voice that disagreement in the conversation, knowing that that partner isn’t even at the table.

So we started what one would call a true partnership. And since then, we’ve always looked, as we grew our organization, to find owners, not employees.

Adler: What that leads to is a lot of what we refer to as “joyously arguing.” We’re good at arguing. We do it a lot, pretty strongly. But in all the years we’ve never actually been angry at each other. We’re just arguing about the stuff, and it’s not about pride of ownership, or “You got the last one, I should get this one,” or “It’s not personal,” or “You always do that.” It’s about, “I think you were wrong because X, and here’s what I think is the right idea.”

We’ve worked very hard to become an organization that argues effectively without it becoming personal. We can have the arguments, and it’s neither personal nor selfish. It’s to get to the best outcome.

Our nightmare would be that we have an employee, and we ask that person to do something, and they thought it was stupid, but they did it anyway. That’s just a nightmare. If you think it’s a bad idea, you should probably raise it and say, “I’m not sure why we’re doing it this way. It seems to be we’d be better off doing it that way.”

Vinnakota: Through serendipity, Eric and I found each other as two people who were comfortable with sublimating their ego to get to the right and best answer. The challenge becomes, as we bring other owners into the organization, especially at the senior management level, that they have similar abilities. And we’ve had to deal with situations where they haven’t been able to do that. And after a while they’ve been gone. They just haven’t fit in.

How do you personally approach leadership at SEED?

Adler: Raj and I were both pretty young when we started SEED, a lot younger than we are now. You very quickly become a symbol for the organization, a symbol for all the constituencies. I remember the first time an employee invited me to something, and I couldn’t go. And my inability to go had an enormous impact on this person.

Every single thing you do as a leader is having an impact on your constituency.

That impact can be enormous compared to anything I imagined in advance of actually being in this position. And I’ve worked very hard to pay attention to that fact since it became clear to me.

Vinnakota: Until you work with people for a long time, they have a hard time with the idea of nebulous reporting structures, especially when you’re dealing with a partnership.

Eric and I are very fluid. That has caused trouble for quite a few people. We decided we work well together with this fluidity, and it is in the long-term best interest of the institution. The people who work with us, especially the senior managers and the senior people at the school, have to get comfortable with that idea. If they don’t, this just may not be the right culture for them. There’s been at least one person, one star, we lost because they just couldn’t get comfortable.

Why is that approach in the best interest of The SEED Foundation? What is it about the partnership that works so well for you both and the organization?

Adler: It just works for us. And it wouldn’t necessarily work for everyone.

We are quite aware that what we do at SEED is a gross violation of nearly every management principal ever published. We are not terribly clear about reporting lines: who reports to Raj, who reports to Eric on which issue. It’s not that we give no guidance whatsoever. But we’re not very clear about it. We get that nine times out of ten that’s probably the wrong thing to do. It just happens to work well for us. I think it has served SEED well because it has served us well.

We were very uncomfortable about it for a long time and felt like we should go in a somewhat more traditional, better-defined route. We found a few smart people to talk to who had done similar things and asked them about it. I remember in particular having a conversation with Billy Shore, who–in Senator Gary Hart’s office before he founded Share Our Strength–had to have a dual leadership relationship. The advice we got was: “If it’s working for you, it’s working for you.”

Vinnakota: We come to better strategic decisions as a result of both of us being involved in the major issues of the institution. There is no way you can be involved in the major issues of the institution if, for instance, I take the full leadership on fundraising and Eric’s not that involved, and then I’m going to ask him to suddenly come in and help with a decision. No, he’s got to be involved as well and understand the nuances, the issues, so that when we have that discussion he comes with a base of knowledge. So, we both need to be in it across many different things.

How would you describe the culture at SEED?

Vinnakota: I would want to differentiate between the Foundation and the schools. I think we’re getting closer over time to having a common culture. We underestimated how important culture was to The SEED Foundation, which was an organization of somewhere between ten and fifteen people for a number of years. We were able to get away with it because it was so small, and we were in a small office. We would be speaking with every single person in the office at least once a day, if not more. People could literally see us exhibiting the values that we wanted: the joyful arguing, the interaction, the debating, the strategic thinking about issues. Almost by osmosis, we were able to do a good job of sharing our culture because we were small enough.

Because we did not understand how deliberate we have to be about culture, The SEED School of Washington, D.C. did not capture that culture. In fact, they only started to capture that culture after a number of years as we became more engaged in making sure that the senior leaders understand how it is we work here at the Foundation. But we learned from that process. Eric and I were very involved in the start-up process at our second school in Maryland, and we were deliberate about “teaching our culture” to the leadership.

Who is involved in the culture-building process?

Vinnakota: The fulcrum here is our Chief Talent Officer, Pyper Davis, and our Chief Schools Officer. They have the responsibility of recruiting and hiring our heads of schools and work closely with school leadership. The roles are of influence and relationship building, because the heads of schools don’t report to them directly. They report to their boards.

Pyper has been instrumental in maintaining the culture at the schools, and we have extended conversations when we think that culture is being undermined.

What are the most important things that leaders at SEED can do to create the conditions for high performance with integrity to be realized?

Adler: I think there are two kinds of organizations in the world: the kind that do what they say they do, and the kind that God knows what they’re doing.

I think the definition of an organization with integrity is one that does what it says it does.

So, if you say you’re there for kids, you’re not actually there just to provide jobs for adults, you’re there for kids. If you say that you’re going to provide a rigorous education, you actually do provide a rigorous education.

To me, the most important thing that we can do to create an organization with integrity is to state our values, intentions, and goals, then be really clear as you go forward that that’s actually what you’re going to do. And to convince everybody that is involved with the organization that you mean it. I don’t know what the rest of the world is doing, but here, in this organization, we mean it. We said we’re doing X, we’re doing X.

We don’t just say it, we do it. That’s what every employee has to experience. They have to be told what the organization is and what it values, and then they have to see, over and over, that really is what the organization does. They have to see employees do that, they have to see the leadership do that. If they see that, then pretty soon they buy it–and they do it. And if they don’t see it, then they know it was just talk.

Is emotional intelligence important for leaders at The SEED Foundation and its schools?

Vinnakota: We have come to understand how critical emotional intelligence and strong self-esteem are to having successful owners. We learned it the hard way.

Eric has very good radar for that. If his radar goes off, basically that candidate is done, it’s over, we’re not going any further. I don’t care if the candidate is the greatest thing since sliced bread. We’ve learned that.

One of our founding school leaders once said, “You know what, SEED celebrates very poorly.” The two of us, by the time we scale that mountain, we’re looking three mountains down. We’re trying to figure out how to get to the next three mountains, and we’ve moved on. We don’t do a good job of celebrating some of our successes well enough. Not only for our own sake and our own emotional quotient, but also for everyone around us.

Adler: We finally forced ourselves to stock the refrigerator here in the office with champagne and sparkling cider so that when a moment arises, we go, “Gee, we really need to just stop, gather everybody together, and do a congratulations moment.” It just wouldn’t occur to us to do it, but people need that.

Has integrity been something that’s been a critical success factor, something you look for in the selection process?

Adler: We probably have an advantage over a lot of the other organizations that you’re interviewing, because we’re a really lousy way to get rich. When you come to work at SEED, you probably have some really good reasons for doing it because you’re going to work very hard and not make a lot of money. That weeds out a lot of people. So, the truth of the matter is that we’re very lucky, that we have a pretty spectacular group of folks, ethically and emotionally speaking, who want to work for us.

Now, that doesn’t mean that you don’t still have to be on the lookout, which I think we always do.

Vinnakota: I think that leadership here walks the walk in terms of the character and expectations we have of the organization and assumptions around transparency and open conversations. It goes back to the joyful deliberation. If we engage in the conversations around pretty much anything, we’re going to quickly figure out people’s character and attitudes.

How do you make sure the shared values pervade the organization?

Adler: Because the schools are managed at a distance, we made the mistake of assuming that people would share our values and our understanding of our mission. Over time, it became clear to us that that was wrong. People don’t just naturally share those things. So, we became more aware of needing to build routines, celebrations, and processes in to the life of the schools that would give us the opportunity to speak about those things, so that they would be heard directly from us.

Is leadership at SEED widely distributed or concentrated?

Adler: SEED has more than 300 employees. The two of us only have so much control, so it better be pretty widely distributed. We better be good at inculcating a pretty wide circle of ownership and management, or we are going to be two very busy guys running around.

Over its history, has SEED ever lost its high performance or hit a plateau?

Adler: Sure. We went through a long period of time where our first school, our flagship, just wasn’t performing as well as it should have. There was no question in our mind that the education the kids were getting there was far superior to the education that would have been available to them in their neighborhood urban public school, but that was hardly the metric that we wanted to use.

We made a few hiring mistakes in key leadership positions. If an employee turns out to be not a great fit for the job, he or she will figure that out and say, “We all know this isn’t working, let’s figure out how I’m going to move out, so this will work out best for me and you.” When what you have is somebody in a significant role who does not have that emotional intelligence to manage the pressure they’re under because they’re ill fitted for the job, you just have a disaster on your hands.

In the end, all of our problems have to do with our adults not being able to do the things that we need them to do.

What has influenced your own leadership development over the years?

Adler: We’ve had some tremendous mentors and role models, but the God’s honest truth is that most of what we have learned, we have learned from making mistakes—and from not making mistakes.

Whatever you do, you learn from it. If you get it right, you learn. If you get it wrong, you learn more. We’ve also sought a lot of advice.

To me, the definition of an entrepreneur is someone who wakes up with fifteen things to do that day, and only knows how to do eight or nine or ten of them, and that’s okay.

We’re okay being entrepreneurs. We’re okay not knowing, because we’re good at arguing, figuring what is probably the best move to make, and if that one doesn’t work, we’re good at trying it and just sticking our toe in the water, and taking some data, and seeing how we’re doing with it, and asking ourselves a little bit down the line whether that might be working, or whether we need to change course. Some of it we just figure out as we go.

++++++++++++++++++++++

Bob Vanourek and Gregg Vanourek are leadership practitioners, teachers, trainers, and award-winning authors. They are co-authors of Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations, a winner of the International Book Awards, and called “the best book on leadership since Good to Great.” Take their Leadership Derailers Assessment or sign up for their newsletter. If you found value in this, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!